There remain a surprisingly high number of woodworkers who do not control the dust in their shops. Of those that do, many are unaware that the filter on their collector may be making their air worse instead of better.

Filters are a tricky thing to think about, especially in tandem with wood particulate size. Scientists have actually studied particulate size that occurs with power sanding and found that most of the particles are over 10µm for grits up to 220. Once over 200, the particulate gets finer, although even with softwoods (which generally generate more wood dust than hardwoods), it is rare to see dust under 1µm. General milling of wood, however, routinely produces particulate from 0.3µm-10µm. For reference, particulate less than 100µm can be inhaled by humans. Particulate between 10-100µm ends up in your nose, mouth, and larynx; while particulate smaller than 10µm goes deep into your lungs and alveoli (which affects how you breathe). Even smaller particulate, less than 0.1µm, can get past your alveoli and into your bloodstream itself.

Your dust collector’s filter would need to have an E12 HEPA or better filter to get even close to dealing with the truly problematic wood dust. An E12 usually meets EN1822 standards of 99.5% filtration down to 0.1µm. A well-fitted respirator with E12 or better filters is a great line of defense, even if you have a well-filtered dust collector in your shop.

With all that in mind, I want to talk about wood dust in general, and our perception of calculated risks. Wood in your lungs and in your blood is bad. There are a host of cancers associated with wood dust inhalation, as well as long term sensitivities and asthma. There are countless studies around the effects of wood dust. Even the medium and low-density white woods like maple and aspen can affect you, not to mention the high-extractive woods that poison you while also cutting off your air supply.

Most woodworkers do not take wood dust seriously enough.

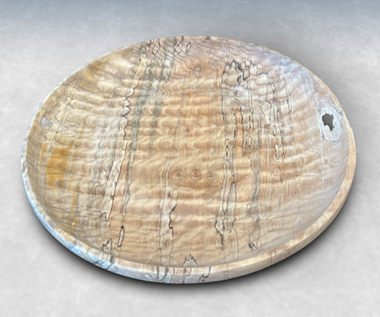

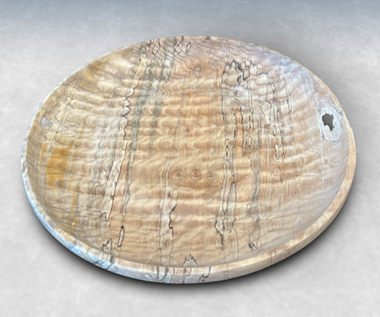

In contrast, most woodworkers do take spalted wood seriously. If you’re unfamiliar, spalting refers to wood that has been discolored due to fungal colonization. It can be brightly colored, have winding dark zone lines across it, or a mix of both. Spalted wood has been used in woodcraft since at least the 1400s in Europe and today is a favorite material of woodturners and box makers. To date, there is not a single published and scientifically verified account of spalted wood being injurious to a woodworker due to the spalting itself.

The Prevailing Myth

Spalted wood is made by fungi, and people take fungi very seriously (think about how much panic there is with a bit of bathroom mold!). There’s a prevailing myth that respiratory protection is required when working with spalted wood because one might inhale the fungal spores and then grow fungi in their lungs. This myth is so prevalent that woodworkers who otherwise would never wear a dust mask will fish one out when working with spalted wood.

The myth of the harmful spalted wood appears to have started from a ‘Notes and Comments’ section in Fine Woodworking (#113, 1995). The then editor repeated a claim previously published in the British Woodturning magazine (by Alec Jardine) that spalted wood spores were very dangerous, and implied they could even infect the human brain. Humankind has long been prone to hysteria around things they don’t understand, the Fungi Kingdom is no different.

Although kingdoms are vast (think about the Animal Kingdom, that includes spiders, dogs, humans, trout, etc.), woodworkers quickly became convinced that spalted wood was a natural human pathogen and that ‘spores’ were to blame. This is nonsense on several levels, including that A) spalting fungi are wood decay fungi, not bathroom mold fungi (consider: spiders are not dogs, just because one is poisonous doesn’t mean everything in the kingdom is poisonous. Heck, not even all spiders are bad!) and B) spalting fungi don’t sporulate in wood, as spores are meant to be carried by the air. Sporulating inside wood would be a horrible evolutionary strategy for reproduction. Most common spalting fungi, the white rots, make macroscopic fruiting forms, like winter polypore and turkey tail.

This doesn’t mean that there are no bad actors on wood, spalted or otherwise. Fungal spores are in the air all the time, and molds do love to colonize the surface of wet wood. You would do well to protect yourself from those—and the right filter will do that for you. Fungal spores vary wildly in size, but as an example, turkey tail (a common white rot fungus) has a spore size of 4.5-5.5µm x 1.5-2µm. Dead man’s finger (makes thick black lines on spalted wood) makes huge 20-30µm x 5-9µm spores. And the blue-green pigmenting fungus elf’s cup makes spores that are 9-14µm x 2-4µm. All of these sizes are in the ‘danger’ category for getting into the lungs, but larger than what could get into one’s bloodstream. They are, however, the right size to get trapped within even a generic HEPA filter (the HEPA rating, regardless of number, usually controls for fungal spores down to 2µm).

To recap, most any HEPA filter can trap fungal spores, but some care must be taken when selecting filters for wood particulate (E12 or better to get that really fine dust). Yet woodworkers willingly don masks to work with spalted wood, but not for ‘regular’ wood.

Why?

I suspect it has something to do with how we perceive risk, and how we value different organisms. When you break out the science, there’s very little difference between the risks of spalted wood and regular wood (in terms of being in your body). Sure, some fungi make secondary metabolites that are sometimes called ‘mycotoxins’ to scare people, and those compounds can be in spalted wood. You certainly don’t want mycotoxins in your lungs or bloodstream, more so because they are foreign agents that don’t belong there than anything else. But some wood species make just as toxic of compounds. Known as ‘extractives,’ (see how that word isn’t as scary?), these secondary metabolites are also toxic to a host of organisms and would be carried on wood particulate, into your body, the same as with the spalted wood compounds.

Both fungi and trees can make secondary metabolites. Both can be broken down into tiny, tiny pieces and inhaled. The fungi that grow on spalted wood are wood decay fungi, many of which are edible or used in homeopathy and traditional medicine. They’re adapted to high moisture contents and wood as a food, so there is little chance of them colonizing you, even if they were still alive when you machined your wood. There’s no real argument to be made for lung fungus colonization. In fact, noting the above, the raw wood particulate itself is far more problematic than any fungi who hitched a ride. Your dust collector’s filters can handle the fungi. They likely can’t handle the wood.

So why don’t woodworkers care as much about wood dust? In the end I suspect it comes down to perception, specifically how we humans perceive danger. Trees are large, visible, and do not move. Wood is dead, inert, and semi-stable. It is very easy to believe that the board in your hands is under your complete control. Trees are just a small section of a vast Plant Kingdom, with a biodiversity that most people feel they understand.

Fungi are their own kingdom entirely. Most fungi do make visible ‘mushrooms’ and generally go unnoticed until a bathroom wall turns black or an old piece of bread pops some green. Fungi always seem to show up where we don’t want them, at least in the home. They’re thought to be more highly evolved than plants and we really have no way of controlling them. For most people, fungi are a mystery. With mystery often comes fear—fear of a group of organisms readily trapped by a HEPA filter.

In the end, woodworking is dangerous on numerous fronts. Both short and long-term damage can occur, from cutting off a finger, to losing your hearing. There’s only so much each person can do to mitigate risk. As you weigh the pros and cons of dust collection (is there a con to dust collection outside of cost?), standard HEPA filters versus E12s, it’s important to keep in mind that your perception of risks might not line up with the current science. You can live without your hearing, you can get by with just a few fingers, but you can’t breathe without your lungs. Taking the (correct) steps to protect them should always be top of your list.

And leave spalting fungi alone. Their only crime is turning an otherwise bland piece of wood into a shock of color.

All work by Dr. Seri Robinson.

Written by Dr. Seri Robinson

Seri Robinson is an associate professor of wood anatomy at Oregon State University and the world’s leading expert on spalted wood. They are also a sculptor and woodturner. Dr. Robinson has written numerous articles about wood anatomy, wood science, and woodturning in publications like Fine Woodworking and American Woodturner. More accessible wood science information can be found in their books, particularly Spalting 101: The Ultimate Guide to Coloring Wood with Fungi and Living With Wood: A Guide for Toymakers, Hobbyists, Crafters, and Parents.